Christo Artist Talk Recap

Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Two people yet synonymous as one. Their souls likely entwined on some astral plane, sharing the exact same birthdates under the sign of Gemini. Since they met in 1958, the pair created artworks all across the world that are nothing short of epic, and although Jeanne-Claude sadly passed away in 2009, Christo continues projects that they conceptualized together decades ago. On November 13, Christo gave a talk presented by the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art at the Holiday Event Center, and while Jeanne-Claude was not there, he carries so much of her spirit that her presence could be felt no matter where he goes. The 300-seat venue was filled to capacity with people eager to see and hear the art legend speak about his current projects, one of which has been in progress for the state of Colorado since the 1990s, as well as early works that have left deep imprints on the trajectory of contemporary art.

At 80 years old, Christo has more energy than people less than half his age. According to the Christo and Jeanne-Claude website, he works 14 hours a day. He is constantly traveling all over the world, managing multiple projects of incredible scale, engaging with contractors, city officials, professors, museum personnel, and the public on a daily basis, and shows no signs of stopping any time soon. Right now he is focused on three upcoming installations: The Floating Piers on Lake Iseo in Italy, The Mastaba for Abu Dhabi, and Over the River in Colorado along the Arkansas River.

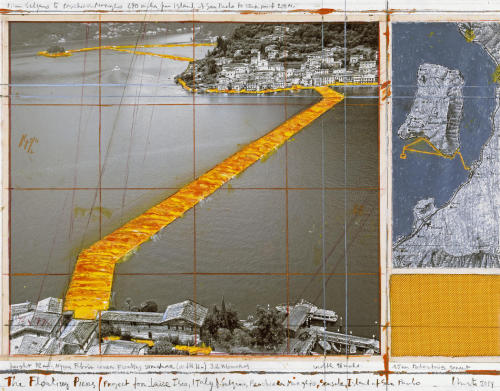

Christo, The Floating Piers (Project for Lake Iseo, Italy), collage 2014, 17 x 22" (43.2 x 55.9 cm), pencil, wax crayon, enamel paint, photograph by Wolfgang Volz, map, fabric sample and tape, photo: André Grossmann, © 2014 Christo. Image courtesy of www.christojeanneclaude.net

Jeanne-Claude and Christo attempted floating piers projects twice but were unsuccessful, but in 2014 he decided to give it another shot. Although the idea of floating piers was initially thought up by the two of them, this is the first major project Christo has taken on solo. In the middle of Lake Iseo is the island of Monte Isola, which is home to 2,000 inhabitants, and the only way they have access to the mainland is by boat. With the completion of the piers, locals and visitors alike will be able to walk across the lake and experience the watery traversal in a new way for the first time. He alternated between topics quickly during his talk, spending a couple minutes talking about old work before switching to something new and back and forth, but his tone and pace would change whenever he talked about The Floating Piers. He spoke with gentleness. Christo and Jeanne-Claude have a long history of creating projects in Italy together, and many of their works shared a theme involving a connection between water and earth. Perhaps The Floating Piers is like a gift to his angel. It will open June 18 through July 3, 2016

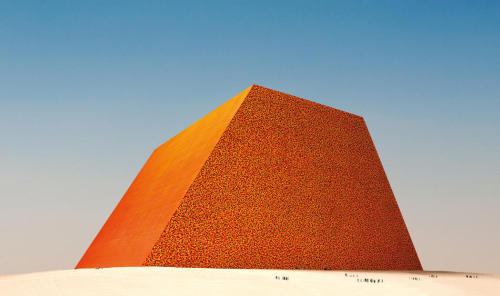

Christo, The Mastaba of Abu Dhabi (Project for United Arab Emirates), scale model 1979, 32 ½ x 96 x 96" (82.5 x 244 x 244 cm), enamel paint, wood, paint, sand and cardboard, Photo: Wolfgang Volz, © 1979 Christo. Image courtesy of www.christojeanneclaude.net

The Mastaba was conceived nearly 40 years ago, and once finished, will be the largest sculpture in the world. It will also be the only permanent Christo and Jeanne-Claude installation. He showed amazing photographs of the duo crossing the towering sand dunes of Abu Dhabi, highlighting their sense of adventure and devotion to immersing themselves in the environments where their art will be displayed. The Mastaba will be made from 410,000 multi-colored barrels and will stand at nearly 500 feet. Constructing a sculpture such as this requires impeccable planning, so they consulted four different engineering professors to prepare plans and studies and decided that the professor from Hosei University in Tokyo had the best strategies for implementation. A date is not set for when this sculpture will be built, but Christo will travel to the region next year to continue its progress.

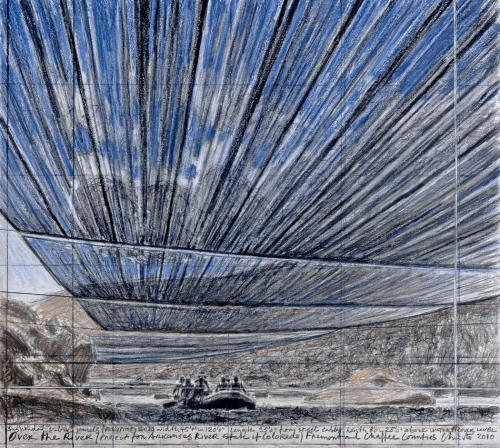

Christo, Over the River (Project for Arkansas River, State of Colorado), drawing 2010, 13 7/8 x 15 ¼" (35.2 x 38.7 cm), pencil, pastel, charcoal and wax crayon, photo: André Grossmann, © 2010 Christo. Image courtesy of www.christojeanneclaude.net

While the audience was captivated throughout the entire talk, it is safe to say that everyone was most eager to hear about the Over the River project. Christo and Jeanne-Claude considered numerous locations for this work, and decided on Colorado’s Arkansas River in 1996. Federal permission to pursue it was granted in 2011. Over the River has been met with much excitement, as well as protest from locals and environmentalists alike, and after a hiatus in 2012, the project is again moving forward. It is likely that Christo was able to do this talk because he was in Colorado to do some related field and/or administrative work. The river rests in a valley and will be shrouded with material that is opaque when seen from the top and transparent when viewed from the bottom, and will cover 5.9-mile spans in eight different locations. Locals feared that the installation would bring too much traffic and congestion to their quiet mountain community, and environmentalists were concerned about how the river’s ecosystem would be impacted. The installation will only be up for two weeks, the material will not cause any changes in temperature or lighting to the water and land below, and everything will be cleaned up and recycled efficiently. If anything a work like this brings public awareness to the environment, and encourages people to preserve it. Citizens of Colorado have been following the Over the River project for years, and will likely draw huge crowds once it is complete, but we still have another 2 or 3 years left to wait.

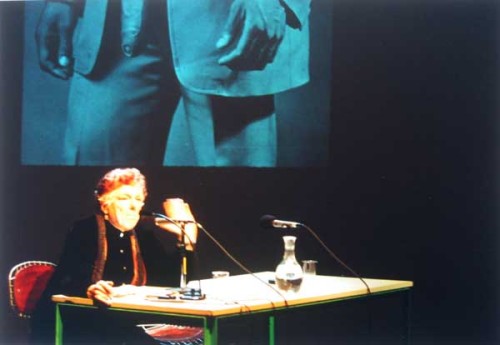

Christo during the Q&A session at Holiday Event Center

Christo dispelled a great amount of information during his talk, which left for a facile question-and-answer session with the audience. People wanted to know simple things, like his favorite color, if he had ever been injured during an installation, the craziest venue he ever worked at, and what advice he has for artists. A young boy asked about his childhood, and Christo gave credit to his parents for facilitating his interest in art by sending him to artist studios and classes at an early age (take note, moms and dads). He approached every person who had a question directly, microphone in hand, never once distancing himself from the crowd. His vigor and affable personality is contagious, and comes through in his (and Jeanne-Claude’s) art. Their art is personal and represents a very particular vision, but it is meant to be shared with the world. Aside from the upcoming Mastaba, all their work is temporary, which adds a sense of urgency for people to congregate and experience it together.

–Hayley Richardson

STM620298; Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri, USA; out of copyright[/caption]

STM620298; Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri, USA; out of copyright[/caption]