Dikeou Superstars: Chris Gilmour’s “Ford (Hot Rod)”

Karl Benz invented the first gas-powered automobile in 1886, but it was Henry Ford’s Model T introduced in 1908 that revolutionized the auto industry. The Ford Motor Company continued to release exciting new models, and in 1932 debuted its Model B and Model 18, which came in several body styles. These models, particularly the roadster and coupe builds, became popular with hot rodders who would tear the car down to the chassis and rebuild with custom engines, exhaust, tires, body mods, and paint. By removing the flash, speed, and signature roar, British artist Chris Gilmour’s Ford (Hot Rod) can easily be interpreted as the antithesis of what a hot rod should be, yet his dedication to the design and build process, as well as his conceptual reinterpretation of “customization,” magnifies the less tangible aspects of what these cars represent. Made entirely out of used cardboard, Gilmour’s Ford truly is one of a kind in a culture that values originality and craftsmanship, and is just one of the many fine examples of how cars have the ability to transform into vehicles of wild creative expression.

Ford is a replica of 1932 roadster with a V8 427 blown engine, dropped front axle, and exposed headers.

Reference images and build process from Gilmour’s studio

Gilmour’s painstaking attention to detail tempts people into thinking this is a real car, and quite often people try to open the trunk or the doors thinking they can hop inside. If there were a set of keys then someone would likely try to start it, despite its obvious artificiality. The contrasts between real and unreal, common material and luxury object, and fragility and solidity, are central to his work and made immediately apparent to viewers in a way that is accessible and delightful rather than confrontational and confusing. Gilmour spends about 3 to 6 months working on one of his cardboard sculptures, and, fittingly, his studio occupies an old car repair shop in a small town in Italy.

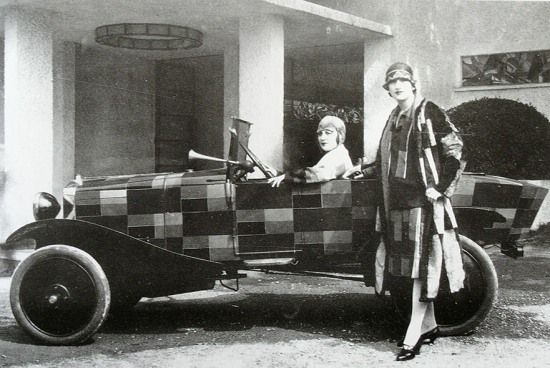

Options were limited for customization prior to Ford’s models of the 1930, but artist Sonia Delaunay was likely one of the first to visually radicalize her car and redefine the automobile as an art object. In 1925 she painted a Citroën B12 with blocks of color to match one of her textile designs. The above image points to the growing popularity of the automobile as something that is not only functional, but fashionable as well. The 1920s was a significant decade for women’s liberation, and Delaunay’s personalized vehicle illustrates women’s increasing freedom and mobility in society.

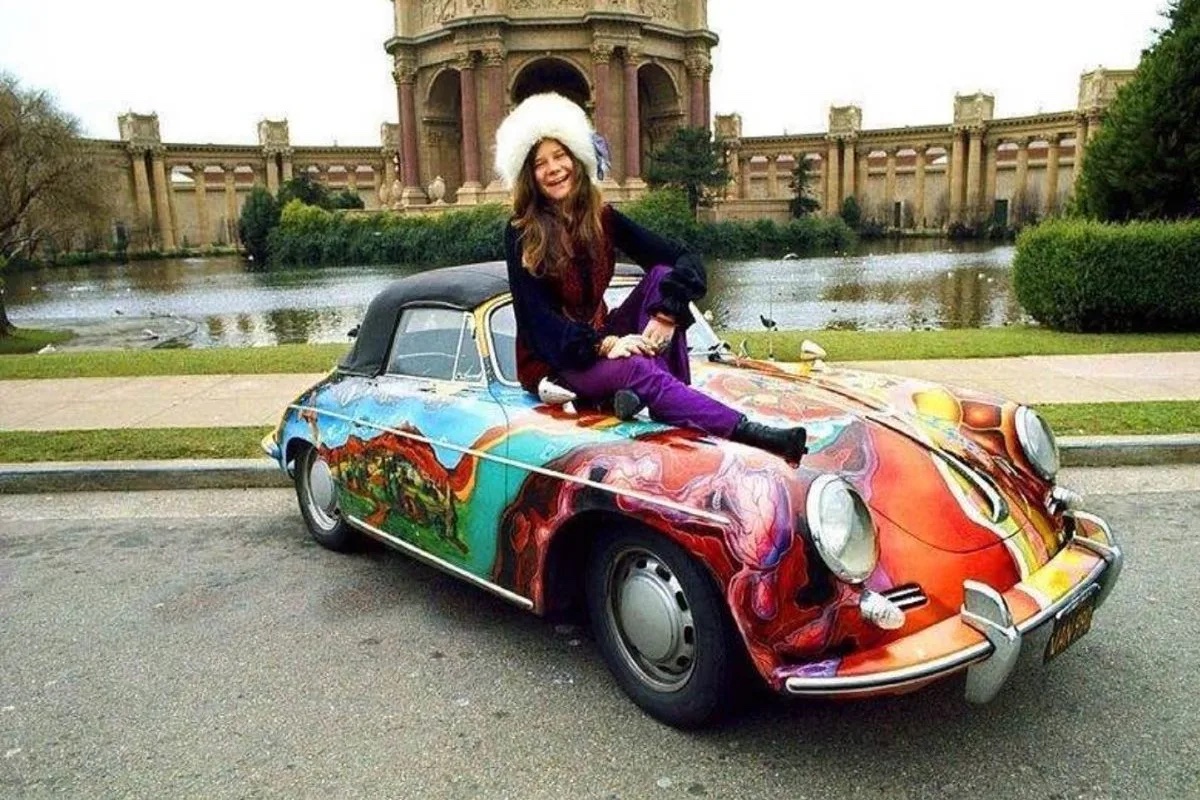

Decorated art cars like Delaunay’s became more common in the 1960s, with the tripped out hippie buses and Volkswagens dominating the aesthetic of the time. Janis Joplin’s 1965 Porsche 356 Cabriolet, painted by San Francisco artist Dave Richards, is an ode to the hippies’ love of color and nature. With rainbows, mountains, butterflies, and celestial bodies elegantly swirling all over the metal body, it’s hard to think of why she would want to trade in this masterpiece for a run-of-the-mill Mercedes Benz.

John Lennon painted his 1965 Rolls Royce Phantom V bright yellow with flowers, making it look like a circus carousel or gypsy caravan, and fellow Beatle George Harrison adorned his 1965 Austin Cooper ’S’, LGF 695D with Tibetan Buddhist imagery. Like Joplin’s Porsche, these cars were painted by talented yet relatively obscure artists. Having their art promoted by celebrities on a mobile platform did much to not only bolster their own profile but that of the art car in general. A decade after the flourish of ’65 celebrity hippie-mobiles, French race car driver Hervé Poulain invited Alexander Calder to paint his BMW 3.0 CSL, thus prompting BMW’s engagement in the arts and bringing the concept of the art car to a broader audience.

Art cars designed by: Alexander Calder, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol and Ken Done

BMW is currently celebrating the 40th anniversary of the art car tradition with exhibitions in Hong Kong, at the Centre Pompidou, the BMW Museum and the Concorso d’Eleganza at Lake Como. “The BMW Art Cars provide an exciting landmark at the interface where cars, technology, design, art and motor sport meet,” reflects Maximilian Schöberl, Senior Vice President, Corporate and Governmental Affairs, BMW Group. “The 40-year history of our ‘rolling sculptures’ is as unique as the artists who created them. The BMW Art Cars are an essential element and core characteristic of our global cultural engagement.” The tradition has tapered off, though, the most recent car designed in 2010 by Jeff Koons. His car, a M3 GT2, is 17th in the series and he adorned it with the number 79 to commemorate the year Andy Warhol created his BMW art car. Each car serves as a symbol of its time, but also shows how the combination of blue chip artists with high-end automobiles creates the ultimate exclusive luxury item. Celebrity artists and celebrity owners are recognized and lauded for their creativity and fashionable taste in cars and the way they choose to customize them, but there are regular, working-class people out there who pour their hearts, souls, and a lot of their income into building their own rides from scratch.

Lowriders represent one of the most misunderstood and stigmatized sects in the world of custom cars. Men and women who partake in this culture are often assumed to be involved in gang activity, but the truth is these people use lowriding as a way to connect with family and build community. Lowriders are typically built from classic American cars of the 1960s, the ’64 Chevy Impala being the most popular model. The technical knowledge and creative vision of lowrider culture is passed down generation through generation. People know each other by what kind of car they drive - what the exhaust sounds like, what kind of stereo they have, and who helped them build it. The car is an extension of personal identity. Aside from the wild paint jobs, custom upholstered interiors, and booming sound systems, what makes lowriders stand out from all other custom cars is the special hydraulic system that gives them their signature bounce, which can reach as high as 8 vertical feet. Anyone who may dispute lowriding as an art form should read the following passage from Dave Hickey, who grew up immersed in car culture and has a firm grasp on its influence on American art aesthetics.

From Air Guitar

Chris Gilmour’s Ford (hot rod) may not have the operative mechanics and other material elements of a real car, but he proves his knowledge and ability to construct such a vehicle with the most minimal of materials. By creating an object of such affluence and fascination out of something as democratic as cardboard, Gilmour challenges the viewer to reconsider their own material desires. A collector of rare and valuable cars would certainly want to add this piece to his collection for its novelty factor while an art collector added it to her collection for its subtle conceptual underpinnings, but both could agree that it is the beautiful craftsmanship that makes it a truly remarkable work of art and contribution to the American car legacy.

-Hayley Richardson