RECAP: ‘Draft Urbanism: A Conversation’ at the Clyfford Still Museum

The theme for Denver’s Biennial of the Americas is ‘Draft Urbanism,’ which means that a city or any urban area is always in a state of flux, caught within a never-ending string of “drafts” that are constantly revised and updated. This applies to the all the different fabrics that constitute an urban community; social, familial, political, economical, cultural, educational, as well as the physical aspects of the urban environment are always changing, even if it’s not always immediately apparent to the human eye.

Architecture is one of the most noticeable indicators of urban change. Structures are always being built, torn down, or remodeled in order to address the needs of the people who use the space as well as those who reside nearby – at least that’s what one would hope. While most new building projects boast large scale and flashy ornament, there is a steady core of architects who believe that less is more. As part of the Biennial programming, the Clyfford Still Museum hosted a lecture called “Draft Urbanism: A Conversation” with avant-garde architects Mark Lee and Michael Webb, who each discussed their perspectives on the architect’s role in the ever-changing urban landscape.

Mark Lee is a partner in Johnston Marklee, an award-winning firm founded in Los Angeles in 1988. To quote their company profile, “Johnston Marklee draws upon an extensive network of collaborators in related fields, engaging the expertise of contemporary artists, graphic designers, and writers to broaden the breadth of design research. Johnston Marklee ascribes to the model of collaboration in which the expertise of joining disciplines are sharpened, rather than blurred, maintaining permeable boundaries for greater results.”

The firm’s Chile House, located in Penco, Chile is a 4,465 square foot pavilion with an enclosed gallery. It is one of 10 projects by different firms intended to help the region rebuild its cultural infrastructure after a devastating earthquake in 2010. The pavilion, set on a forested hill, has two entrances and two large sliding windows that offer views of the ocean and of the city. This open viewing format allows visitors to experience art in an unusual space, but still reminds them of the natural beauty of their surroundings and of the progress made toward revitalizing their city.

They even used the shape of the tree trunks as inspiration for the formation of the concrete walls, showing that contemporary architecture can be harmonious in nature. The pavilion looks otherworldly, but still allows those interacting with the space to feel like they’re on Earth by allowing open views of the land, sky, and sea, as illustrated in the diagram above.

The other project Lee discussed was this Hill House (2004) in Pacific Palisades. Southern California has some of the strictest building and zoning codes in the country because of the dense population and steep hillsides that are prone to horrific mudslides and earthquakes. The challenge was to build a single-family home on an irregularly shaped hillside. The family also wanted a reduced environmental footprint, prompting the architects to focus their design vertically rather than horizontally. The project succeeds in maximizing interior volume and minimizing foundation area, all while perched on the edge of a steep slope. From this angle, the home looks like the head of a screaming Lego figure, but the inside is super sleek and polished.

There are three floors: downstairs bedroom, main floor common area, and third story loft with a library. While the design and exterior view of the house is distinctly vertical, the interior flow seems predominantly horizontal, thus transforming a person’s presumptions about the space upon entering. If one takes a moment to do a little browsing on the web for other Johnston Marklee projects, it will be immediately apparent that the masterminds behind this firm are fully dedicated to re-approaching and reconfiguring the ubiquitous ‘white cube’ in contemporary architecture and urban design into something that can fit any location and lifestyle.

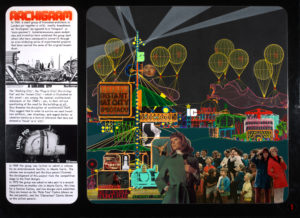

Michael Webb gave a follow-up presentation that delved into topics and imagery that seemed more geared for space travel than urban architecture. Michael was one of the founding members of Archigram, which formed in the 1960s as an avant-garde architectural group out of London; Webb now lives and works in upstate New York. Dedicated to hi-tech, futuristic, and conceptual (i.e. impossible) projects, Archigram made a name for itself in the architecture community as a group that did not limit itself to the confines of environmental reality.

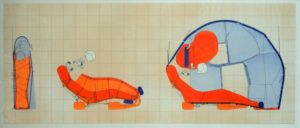

One of the first Archigram projects Michael discussed was the Cushicle, a combination of a cubicle and a cushioned recliner. The design illustrations show the participant wearing the Cushicle like a standing sleeping bag before it inflates and allows the participant to recline and actually live within the enclosure.

This is what the Cushicle looks like when it is inflated.

And this is what it looks like after. The participant is then supposed to gather the loose material and somehow re-wrap it around themselves so it’s back to the sleeping bag configuration. The Cushicle is not just for sleeping and comfort, but it is supposed to serve as a total living environment. To quote from Webb’s website about the project, “The Cushicle carries food, water supply, radio, miniature projection television and heating apparatus. The radio, TV, etc., are contained in the helmet and the food and water supply are carried in pod attachments.” This is not your traditional architecture with walls, windows, and rooftops – this is human habitation reinvented. It is meant to address issues of urban sprawl and life of the contemporary nomad. He questioned why people need such protective buildings when we live on such a benevolent planet. Well, a lot has changed from the 1960s up until 2013, and it is pretty safe to say that Mother Earth is not as benevolent as she used to be.

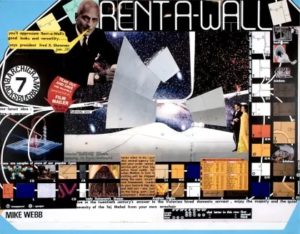

The next project Michael presented was the Rent-A-Wall. He did not talk a whole lot about what this particular project is about (or maybe I just can’t remember what was said), but he did use this image to illustrate the idea that “you don’t have to tell to the truth in architecture.” At this point in the lecture Michael focused on the visual aspects of his designs. It must be noted that almost no Archigram project has ever been fully constructed, outside of one-off prototype models. However, the six men that comprised Archigram are highly recognized and praised for their incredible inventions in architecture and design, their advancements in the educational field, and their beautifully crafted illustrations. I was mesmerized by the images Michael showed during his presentation, with their rich collage aesthetic featuring cool combinations of sci-fi graphics, ‘60s advertisements, and modern typography. These “blueprints” are at the heart of the Archigram legacy. These images are not just instructions for futuristic living, but works of art in their own right.

In 1963, Archigram was invited to do an exhibition of their “Living City” project at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London. The exhibition then traveled to the Manchester City Art Gallery and the Walker Art Gallery, Cambridge. Archigram was so involved in the artistic side of architecture that they even opened their own gallery space, Adhocs, in the early 1970s.

Archigram disbanded in 1974, but each of the six original members is still working in their field. Michael has taught architecture at Rhode Island School of Design, Columbia University, Barnard College, Cooper Union, University at Buffalo and Princeton University. He also still works on his illustrious designs and his “Two Journeys” project has been exhibited in the United States and Europe.

There was a question-and-answer segment at the end of the presentations. Only a few were brave enough to raise their hands in the crowd, and out of those few only one person asked a coherent question. Even though Mark Lee and Michael Webb had only been in Denver for barely 24 hours, they were asked what they thought of Denver’s urban landscape and what they think could be improved. Michael said that we could stand to have some infrastructure improvements and better coordinative planning. Mark said the city of full of architectural gem/icons, but the common, “everyday” structures like offices and apartments are not of the same quality and do little to support these icons. I agree with this statement, but Denver has some amazing historical neighborhoods and buildings that I am sure they did not have time to see.

These two men and their respective colleagues represent the razor’s edge of contemporary architecture, but both have completely different approaches. While Mark Lee comes from a perspective that envisions a home on a specific site, Michael Webb totally questions the entire idea of “the home.” What is a kitchen? What does it mean to sleep in a bed? He believes buildings shouldn’t even exist unless people are in them. That seems like a challenge for the folks at Johnston Marklee, and for all architects across the world.

-Hayley Richardson

July 31, 2013