[caption id="attachment_4771" align="alignnone" width="500"] SONY DSC[/caption]

SONY DSC[/caption]

Joshua Abelow with his Call Me Abstract (Self Portrait at Age 36) grouping.

Joshua Abelow is a Maryland-born, New York-based artist who is represented by James Fuentes Gallery in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Curating is an extension of his practice, and he has not only created spaces for himself to work and exhibit, but spaces that open doors to many other artists as well. Currently living in a defunct church in Harris, (a small town about two-hours drive north-west of Manhattan) Joshua has made a studio-living space for himself, as well as “Freddy,” his curatorial project space to exist in a permanent manner. Abelow received his BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design and his MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art. We were fortunate to have his company last week for an event at Dikeou Collection and show him what the Front Range is all about.

Wednesday, May 25

Joshua Abelow calling himself in front of his Call Me Abstract (Self Portrait at Age 36) grouping.

After picking up Joshua from Denver International Airport, pointing out Luis Jiménez’ great blue mustang and all of the peaks visible from I-70, Dikeou Collection Director Hayley Richardson, Joshua and I went to eat a late-afternoon lunch in Denver’s Highlands neighborhood. Being a little nervous and only having one very tight parking space available, I was unable to parallel park, extending the time between parking and eating. Joshua promptly offered to park my car for me and in the most graceful fashion, swooping my car into this tiny space and expediting the relief of our hunger pains all while impressing us with his fine use of angles.

As this trip was Joshua’s first time to Colorado, we had to begin the sightseeing close to home and showed him around the Dikeou Collection, with the tour culminating within the room that houses his grouping of oil on burlap canvases, Call Me Abstract (Self Portrait at Age 36).

Thursday, May 26

Conversation at Dikeou Collection.

Joshua and Hayley kick off the conversation.

At noon, Hayley, Joshua and I all met at the Dikeou Pop-Up: Colfax. Showing Joshua around the space, we talked about his fellow Fuentes Gallery artist Lizzi Bougatsos’ work featured in the space, as well as works by Sarah Staton, Rainer Ganahl, Anicka Yi, and Devon Dikeou. After learning more about Joshua’s written work, we headed to Cap City Grill for a quick bite before going to Denver’s unique Clyfford Still Museum. After falling for Clyfford’s work all over again, we brought Joshua back to Devon’s loft for a brief rest before the event later that night.

On the way to the loft, Joshua says, “Wait! Pull over really quick!” As it turns out, he spotted fellow New York Fuentes artist Jonathan Allmaier and his wife and artist Maria Walker. Pulling the car over there was a lot of “Oh my god” and “What are you doing here” exchanged. Sitting in the middle of the street with my hazards blinking and cars patiently waiting behind me, I realize how small the U.S. art community is. Two people represented by a gallery with 19 artists on its roster can run into each other 1,800 miles away. Later in the evening, Jonathan and Maria joined us for the conversation and experience the collection.

We prepped for the event - put out food, set up chairs, mics, the whole sha-bang - and soon enough it was 6:30pm and time to let people into the collection. After mingling with Denver artists, curators, students, and app developers, the event began. The conversation covered so much of Joshua’s work, from his “art blog art blog” to his gallery spaces and of course his paintings, drawings and well maintained practice. For me, the most interesting topic was the documentation of his art blog. This documentation manifested as an independent art object, which included a flash drive, clever packaging and the ingenuity of creating a commodity object around a blog as something that is typically open and available to the public.

During the Q/A session a really great question was asked about an artist’s existence in social media and whether or not it is a requirement to be seen adequately in the art world. Joshua, running a long-running art blog and having a heavy Instagram presence, is a great artist to discuss this subject as he literally created an art object out of his social-media presence. His answer to this young woman’s question was that it helps an artist get more viewership of their work but it can also be self-deprecating. Because of his first hand experience with this dichotomy, he references this self-deprecation a lot in his work.

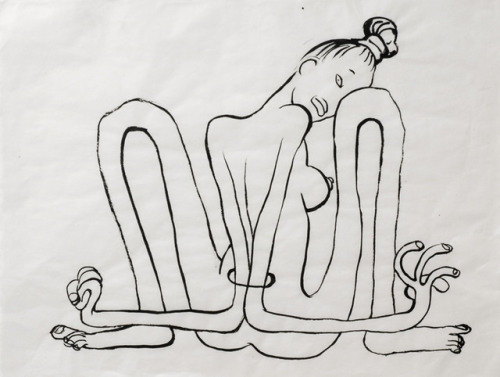

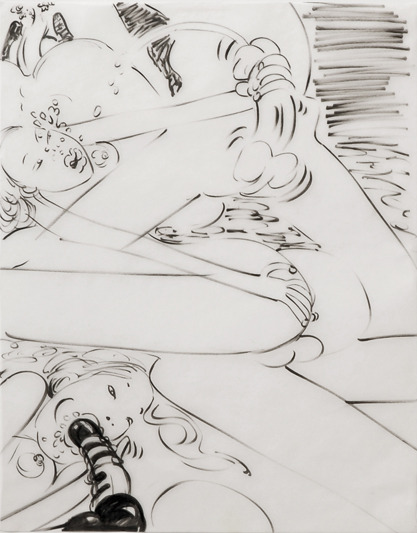

Installation view of Abelow’s Running Witch series.

Focus in the conversation was also drawn to Joshua’s Freddy character. Freddy takes the form of a running witch in most of Joshua’s current works. He explains his interest in Freddy as an idea that something can exist in your dreams and also pervade your everyday life, much like the internet and social media. Freddy is also a play on words for his hometown Frederick, a joke he and his sister share. There is a sort of magic in merging various times, spaces and realities which painting can do through existing in the gallery space, the internet, and digitally. This transitory magic also carries symbolism and metaphor, and he refers to its importance not only in the art world, but specifically painting.

Friday, May 27

Dikeou Collection Director Hayley Richardson and Joshua in a cabin up at Lake Echo.

Joshua in the renovated Georgetown schoolhouse.

As a reward for our successful evening, we decided to treat ourselves with a day in the Rockies. Our first destination was Red Rocks Amphitheater in the foothills of Morrison, Colorado. Once we parked and approached the entrance, we were told that one of the most unique music venues in the world is closed early for a concert… Our next attempt was Mt. Evans, which has an elevation of 14,265 feet (AKA a “fourteener), one of the few that is driveable to its summit. Again, we got about halfway up the mountain before closed gates informed us that the road was not yet accessible. Undeterred, we strolled around Echo Lake near the base of Mt. Evans, getting our altitude bearings before going back on I-70 and hitting Georgetown. By the time we reached Georgetown, the clouds parted and allowed for a nice walk around its historic neighborhood. It wasn’t long until we stumbled into a recently renovated schoolhouse which now serves as a cultural center for the town. Returning the building to its former glory, this remodel created a similar space to Joshua’s church, allowing for a cultural hub in a rural town. After meandering through Georgetown’s historic neighborhood, ooh-ing and ahh-ing at the late-nineteenth century houses, we returned to Denver, stopping through Golden to catch a whiff of the classic Coors scented hops in the air.

Saturday, May 28

Rockies game selfie. From left to right me (Madeliene), Denver Artist Derrick Velasquez, Hayley and Joshua.

Hayley and Joshua with Dinger at Coors field.

Joshua killing us at pool.

Good ole family fun was the theme of the day with pizza, baseball and pool. The Denver Rockies were sadly defeated by the San Francisco Giants at Coors Field, but it was still a perfect day to relax outdoors and enjoy America’s pastime. We later meandered to El Chapultepec, a nearby bar and Joshua proved to be quite the pool shark. Whether expressed through his art, parallel parking, or pool skills, Joshua knows his angles.

We would like to extend much gratitude to Joshua Abelow for coming to Denver and being a wonderful guest and, despite the altitude, accompanying us for a much-needed retreat to the mountains. Next time we hope he brings his adorable dog Georgia along for the journey.

Additionally we would like to thank Veronica Straight-Lingo for featuring Joshua Abelow and Hayley Richardson’s conversation on KGNU’s Metro Arts broadcast last Friday. The clip can be found here: http://www.kgnu.org/metroarts/5/27/2016. The segment on the Dikeou Collection and Joshua Abelow begins at 15:16.

Joshua’s website can be found here: http://www.joshuaabelow.com/

Come join us for more events this month!

Saturday, June 4 - Family Saturday Workshop: Paul Ramirez Jonas Sound Art Workshop at Dikeou Collection, 12-4pm

Thursday, June 16 - Video Dialogue: Rainer Ganahl at Dikeou Pop-Up: Colfax, 7-9pm

Friday, June 24 - Fresh Jazz & Crisp Vinyl Series with Paramitcha at Dikeou Pop-Up: Colfax, 7-10pm

-Madeliene Kattman

SONY DSC[/caption]

SONY DSC[/caption]