Fine Art and Fashion: Claude Montana and Stephen Sprouse

In the 1980s and 90s fashion found new media via the art museum, inciting blockbuster exhibitions celebrating the work of great designers at major institutions. These monumental and collaborative shows have prompted a discussion which frames fashion within the history of art. Consideration of clothing as cultural artifacts that belong to larger artistic trends, and which convey complex messages about social identity, dissolves the distinction between fashion and art. Since early this year, Dikeou Collection staff have been working to archive curator Devon Dikeou and her mother Lucy’s fashion collections. In line with Dikeou Collection’s larger archiving initiative, the project has been a vast undertaking involving shipping items from three different cities, photographing each individual garment, organizing them by rack, compiling a database, producing tags, and creating a permanent space to store the collection. Perhaps because of the recent revival of 1980’s and 90’s trends in fashion, a few dark horses among this assemblage, by Claude Montana and Stephen Sprouse, have stood out from the Gucci, Armani, and Chanel, as compelling and relevant objects of material culture—vestiges of once thriving 80’s designers who briefly became stars, failed financially, and struggled personally, but left a long-felt impact on the world of fashion design.

Like many of their contemporaries in France and America, both Claude Montana and Stephen Sprouse’s careers came about in the aftermath of a runway show that took place in 1973, known today as the “Battle of Versailles.” American designers Bill Blass, Stephen Burrows, Halston, Anne Klein, and Oscar de la Renta presented collections in opposition to Pierre Cardin, Hubert de Givenchy, Yves Saint Laurent, Christian Dior, and Emanuel Ungaro. The American shows were studded with celebrity appearances. Broadway darling Liza Minnelli opened and closed the program. Warhol Superstar, Jane Holzer, walked for Oscar de la Renta. With minimal stage props and an emphasis on human movement, the presentation was fresh and contemporary in contrast to the over-the-top vêtements and exhaustive spectacle presented by the French. The Americans left the victors, ushering in a new era in fashion.

Claude Montana Black and Racing Car Green Wool Jacket

Just two years after the 1973 runway show at Versailles, Claude Montana, then twenty-eight, entered the scene among the ranks of Thierry Mugler, Jean Paul Gaultier, and Kenzo Takada. Together they responded to the need for something new in French fashion. In line with this revolutionary moment, Montana’s ready-to-wear looks were marked by the re-emergence of materials like wool and raw leather, and an insistence on geometric volume. The sturdy fabrics and distinct lines of his clothing presented a stark contrast to the frilly and feminine norm. One of many theatrical runway shows, Montana’s 1988 Bicentennial in Sydney demonstrated the extent of his innovation. Electric blue spotlights pressed down on the stage, pyramidal structures of light in otherwise complete darkness. Puncturing the stillness, loud and startling sounds of Australian birdcalls—an apparent inspiration for Claude’s collection—reverberated through the space as androgynous and lithe female figures jauntily cut across the catwalk, moving with the same sumptuous angularity as the structured jackets they wore. Breaking the blue-black reverie of parading pale-faced models, one commentator muttered, “these women are wearing sculptures.” The observation is quite precise. The geometric emphasis, and saturated hues in his runway and prêt-à-porter characterizes the gabardine jacket by Montana in Devon Dikeou’s collection. Racing-car-green, cropped short, and embroidered with a black zig-zagging pattern that extends from the collar, it looks like something that could appear on the pages of Vogue today.

While Montana was reviving French Fashion from the wreckage of the infamous 1973 Versailles show, afore-mentioned American designers Bill Blass and Halston were already working with the young innovator and artist Stephen Sprouse, who started his career in fashion at the age of fourteen. After his first trip to New York, Sprouse was deemed “boy genius” by influential fashion columnist Eugenia Sheppard, given a summer internship with Bill Blass, and then a position as Halston’s assistant in 1971. It was during his time at Halston that he met his artistic champion Andy Warhol, and started dressing his neighbor Debbie Harry. When Sprouse left Halston to work independently he created looks for Blondie, fraternized with artist Chuck Price, created large scale Xerox collage compositions depicting Edie Sedgwick, and painted chartreuse, violet, and vermillion portraits of deceased rock idol, Jim Morrison as Jesus. In 1983, Stephen presented a small collection at Kezia Keeble’s show of up-and-coming designers, in promotion of the launch of the new Polaroid SX-70 camera. The collection of bright Day-Glo clothing had 60’s-inspired shapes and featured the designer’s own hand printed across the fabric like graffiti.

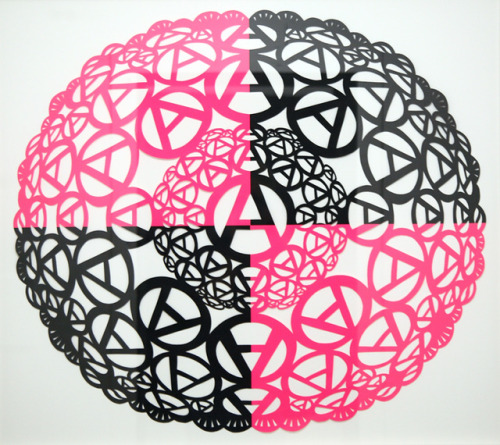

Stephen Sprouse Neon Warhol Cotton Skirt

By the time Sprouse released his third collection in 1984, Andy Warhol was trading him paintings for clothing. Sprouse later moved his studio to the location of the old Warhol Factory. The move is partly to blame for his company going bankrupt that same year. When Sprouse opened a new store on Wooster Street in 1987, his artistic idol Andy Warhol was dead. Sprouse apparently walked around the opening of his SoHo store clutching a self-portrait of Warhol that the artist had given him years before. At this time, Sprouse started producing clothing printed with Warhol’s paintings. As is exemplified by Devon Dikeou’s Andy Warhol skirt, these brightly colored pieces recalled Sprouse’s early Day-Glo aesthetic. The 1988 pieces that Sprouse produced are now some of the most coveted by collector’s; however, they did not receive immediate success. Again, Sprouse was forced to close his stores.

Montana and Sprouse had distinctly different styles, and stories, but both grappled with the same struggle: to succeed as a business. They failed financially almost as abruptly as they rose to stardom. While Claude Montana experienced unprecedented fame in the Parisian fashion world in the 1980’s and early 90’s, he is best known today for his personal and financial tragedies. Montana’s fashion house filed for bankruptcy in 1997, just one year after his wife and muse, Wallis Franken, committed suicide by jumping out of their kitchen window. Over the course of his career, Stephen Sprouse relaunched his company five times, and struggled to establish himself as a fine artist. These hardships seem to define the legacy of a young man who caught the eye of the New York fashion world as a fourteen-year-old, and earned the admiration of Andy Warhol. Because of his artistic influences, Sprouse brought the street styles of pop, punk, and grunge to the fashion houses. Montana’s shows blurred the boundary between runway and performance art, and his garments became sculptural expressions of the contemporary woman.

2 of the 21 garment racks that occupied Devon Dikeou’s loft this summer during the archival initative, with one of Warhol’s Mick Jagger prints above

While placing items from Devon Dikeou’s collection by Montana and Sprouse on the same rack may at first seem like arbitrary categorization, based on the decade they belong too, consideration of both designers’ distinct styles and stories in juxtaposition prompts a broader discussion of the artistic context they came out of. It all started at Versailles, and even in France, it seems that Warhol’s influence was everywhere.

- Rebecca Manning