Dikeou Superstars: Tracy Nakayama

It is no secret that the world’s history is largely shaped by the perspective of men, and this naturally applies to our understanding of art as well. Women have always participated in the visual arts—whether that be creating, collecting, teaching, or theorizing—yet their contributions are relegated to the sidelines while their male counterparts have been heralded as the apogee of artistic greatness. The feminist movement of the 20th century gave women the power and mobility necessary to gain recognition and respect for their cultural achievements, and the footing to express themselves and their worldview creatively. Tracy Nakayama applies “the female gaze” toward a subject that generally ignores any possible enjoyment or consumption by women—pornography—and thus flips the script on what these images look like and who they are intended for. Her series of watercolors at Dikeou Collection convey a sense of sweetness and flirtatious ease during erogenous encounters that appeal to females sexual interests, but there’s a raw edge left intact that can seduce women and men alike. Nakayama is representative of a growing number of female artists with a direct approach to nudity and sex, and who seek to disprove the notion that this kind of carnal imagery cannot exist without misogynistic undertones.

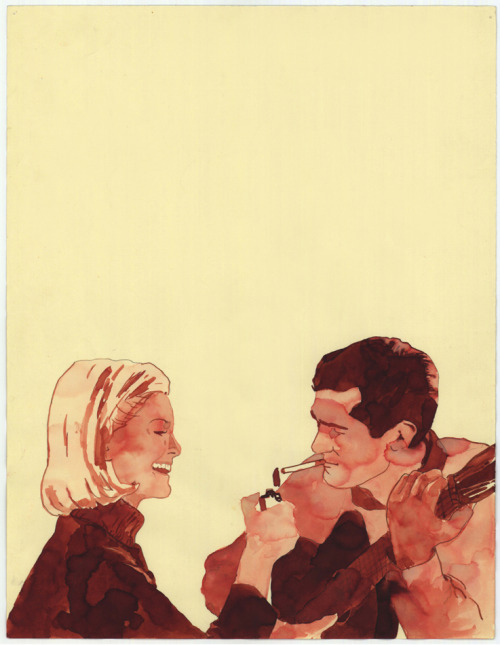

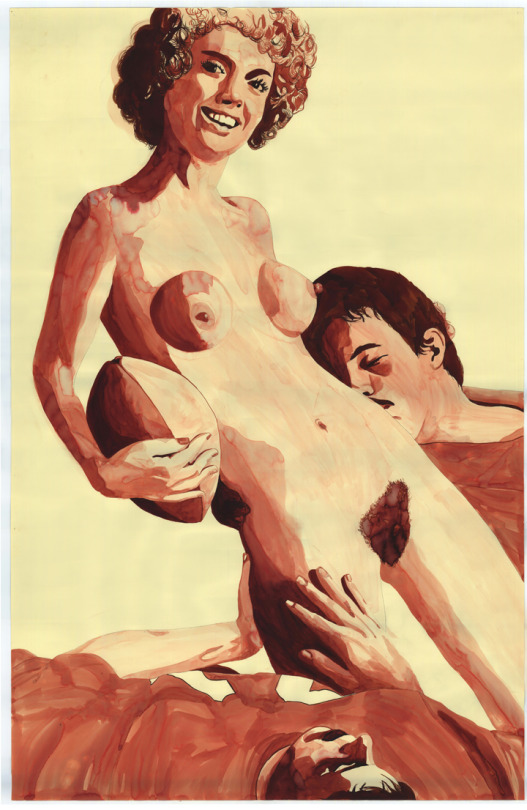

Nakayama composes her paintings like a collage, incorporating poses, objects, and scenarios she finds from her large collection of vintage pornography from the 1960s through 1980s. As a cheeky twist, she uses the faces of people she knows on her figures as a personal albeit untraditional sign of affection. For example, the face of the woman in her large painting, Football, is that of her own mother, smiling gleefully as two mustachioed men in jerseys caress her body. The woman holds a football under her arm like the player on the Heisman Trophy, hinting that she’s the one who will come out on top in this game. Perhaps her mother owned a copy of The Joy of Sex that Tracy maybe discovered during her adolescence, and the illustrations by Chris Foss ignited some inspiration for her artistic pursuits. The combination of the vintage references and sepia color schemes makes Nakayama’s work strongly reminiscent of a time when the peak of feminist action was met with a new era of free love, spawning the Sexual Revolution which motivated female artists to depict sex and sexuality in ways women never had before.

The female nude is one of the most popular subjects in the history of art, a favorite of male artists in particular. Alice Neel presented a whole new perspective on this subject by removing the sexualized and idealized views cast upon the model. Her paintings revealed not only the bodies of her sitters in a more natural way but their psychological states as well. Neel was one of the first to paint pregnant nudes, and also did a self-portrait in the nude at 80 years old. She applied the same techniques to her male nudes, too, where they exuded the same vulnerability and true to life form. This focus on gender equality is prevalent in the work of English painter Sylvia Sleigh, who made gender-reversed versions of famous paintings like Ingre’s The Turkish Bath. Sleigh’s male nudes are more idealized than Neel’s, implementing the tactics of the male gaze onto male subjects and pointing out the problems of gender bias. Joan Semmel paints nude self-portraits from her own perspective so her face is invisible, which leaves the viewer to draw their own conclusions about how identity is constructed and recognized via the normally covered and private body.

Artists like Alice Neel, Sylvia Sleigh, and Joan Semmel were key figures in the progression of the female vision and sex-positive movement in the arts, while women like Betty Tompkins and Marilyn Minter push the envelope even further by depicting sexual acts and genitalia explicitly and unapologetically. Like Semmel, Tompkins and Minter remove the identity of their figures, as well as context, putting the viewer on the spot to make their own judgment calls about what the body parts themselves represent. When reduced to individual components like a machine, these bodies are performing exactly how they’re supposed to, yet art like this is still very challenging for even the most savvy art appreciators. If placed along a spectrum, Tracy Nakayama’s watercolor collages would sit comfortably between the avant-garde nudes of Neel, Sleigh, and Semmel and the pronounced emphasis on sexual parts and performance of Tompkins and Minter. As a respectful gesture toward our diverse audience at Dikeou Collection, Nakayama’s paintings are exhibited within a special enclosed gallery. The room is like a secret little love nest where Tracy’s works can be reveled privately or in the company of that special someone. When people exit the room and shut the door, the figures in the paintings can bask privately themselves in sensual bliss.

-Hayley Richardson