Dikeou Superstars: Chad Dawkins

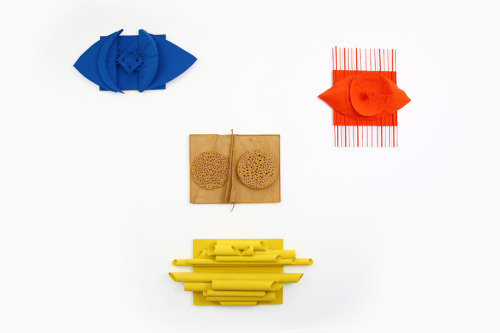

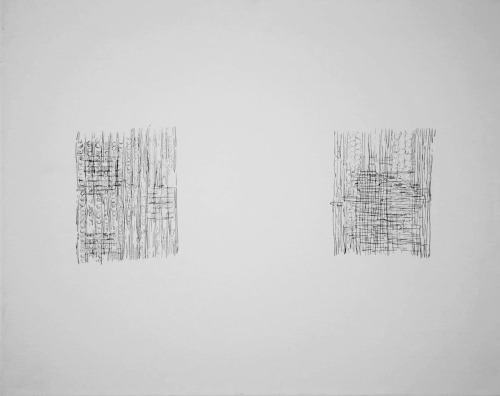

Originality is difficult to define in a time when we are inundated with content that is quickly edited, rehashed, and spit back into the information cycle machines. Artists searching for inspiration can easily slip into a habit of unconscious mimicry, resulting in work lacking in authenticity. Instead of trying to “force” originality, Chad Dawkins critiques the concept through reproduction. His work Untitled, #149-168 at Dikeou Collection is a series of 20 graphite drawings on canvas that copy engravings of microscopic plant cell images from the 19thcentury. He describes the works as “handmade reproductions of mechanical reproductions of handmade reproductions of something viewed scientifically…” and through this ongoing process of reproduction, he concludes that “inevitably they are different” from their original counterparts.

Formally speaking, the work is subtle and minimal yet painstakingly detailed and spatial in its presentation. These discernable paradoxes underscore the circuitous meaning of the work where the question and the answer are one in the same. In his artist statement, Dawkins notes that he received the prints he copied from as a gift, and, in a somewhat symbolic vein of the work, he gifted the drawings to Devon Dikeou. They were originally exhibited at the Dikeou Pop-Up Space on Bannock Street from 2011 until 2013, and are currently on view at the main Dikeou Collection gallery on California Street in the same room as Nils Folke Anderson’s Untitled (California)styrofoam sculpture. This is a wonderful pairing because they both play with this idea of paradoxes. Themes of control vs spontaneity, consistency vs variety, and the idea that the finished piece(s) leave traces or ARE traces of what’s been play into both these artworks.

“MAMAS DON’T LET YOUR BABIES GROW UP TO BE COWBOYS”

2009 ongoing

Wall: 2 Chad Dawkins Drawing that the Artist Curated into Her 11.1 Artpace Residency

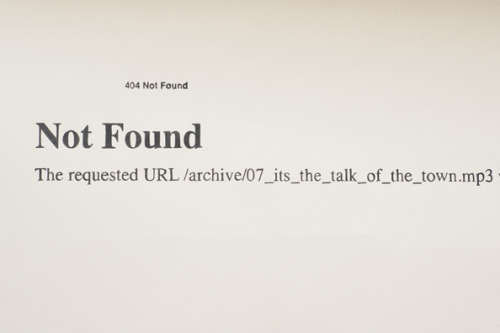

The Drawings’ Language and Font Replicates the Message Found when Searching for Simmons’s Recordings on the Internet

Detail: Left, “It’s the Talk of the Town”; Right, “Round Midnight”

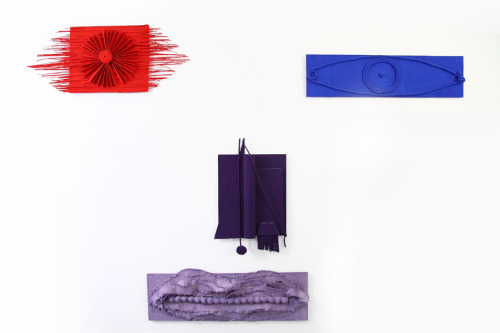

Dawkins’ reproduction drawings can also be seen in Dikeou’s installation Mamas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to be Cowboys, a work which looks at great jazz musicians and whose names have been embossed into music history and those who have been glossed over, the focal figure being saxophonist Sonny Simmons. As a contribution to the installation, Dawkins created two drawings that copy an internet error message stating that Sonny Simmons’ music cannot be found at the requested server – a testament to the musician’s underrecognized place in the jazz pantheon.

Dawkins’ 2010 exhibition self-titled at Sala Diaz in San Antonio featured a reproduction of a photograph of painting, as well as a reproduction of the painting in the photograph. Dawkins stated, “Primarily, the exhibition assumes a conceptual role of a postmodern critique of the modernist tenets of object making, the cult of originality, and the sanctity of artist’s objects. Ultimately, these critiques, (at this point) being rooted in unoriginality, serve the purpose of testing their own validity.” The two phrases that stand out are “cult of originality” and “testing their own validity,” each coming off with a bit of a satirical eye-roll and a fair challenge in both the creation and critical response of art making. In the case of Untitled, #149-168, the viewer is never told that the drawings are reproductions, leaving them to assume that they are in fact original images. However, many are able to discern that they are depictions of something on a cellular level, and the originality of both the primary source and its replication are never questioned or argued.

-Hayley Richardson