Dikeou Superstars: Lawrence Seward

We are now officially in the throws of winter. It starts out as a joyous and enchanting time of year with glittering snow and hot cocoa but eventually slumps into long cold months of dirty slush puddles and expired eggnog. Let’s face it: winter sucks. Unless, of course, you’re fortunate enough to be able to travel or live some place warm and tropical and can avoid the wintertime blues. Lawrence Seward is one of those lucky individuals who was born and raised in Hawaii. He attended school at NYU, but has since moved back to the Aloha State and now teaches at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu. His artwork at Dikeou Collection gives a glimpse of the island life from a local’s perspective, which, in reality, is not all rainbows and tiki drinks like we may expect.

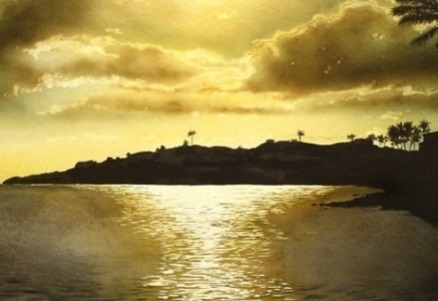

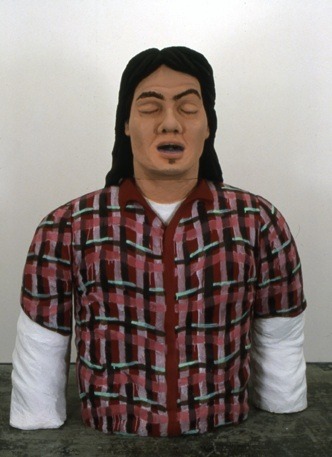

Upon entrance into Seward’s room at the collection, the viewer is confronted with an oversized self-portrait of the artist made of foam, paint, and plaster. This work was made in 2001 but titled 1989 and is meant to depict himself from that period in time. His long hair and casual flannel are indicative not only of his laid-back personality but of the easy-going environment in which he lives. A little island scene with a golden sky and palm trees is hidden inside his mouth, complete with pearly grains of sand upon his tongue, as if he carries a taste of Hawaii with him wherever he goes. Sculptural self-portraits are not very common, especially in this size, but there is a tranquil quality to this work that does not make it self-aggrandizing. The sculpture faces a wall that is hung with twelve different drawings and watercolors by Seward that depict various Hawaiian themes like sunsets, surfing, luaus, and tiki paraphernalia, but a thoughtful analysis would lead one to see that these images portray a visitor’s paradise at the local’s expense.

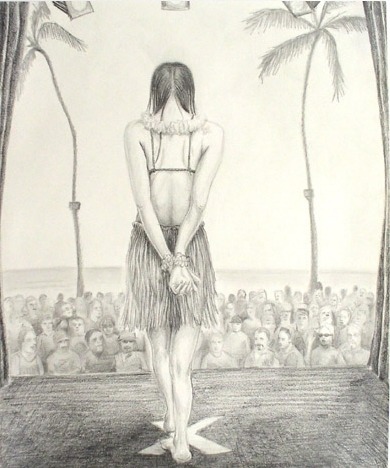

Barbed wire, concrete walls covered in graffiti, and steel beams frame ocean waves and sandy beaches in several of these works. The largest depicts a surfer impaled by his board and left for dead on the beach which, as Seward says “evokes suicide, sacrifice, mishap, and the death of youth.” Other drawings show ukulele players and Hula dancers from the back as they entertain a crowd of tourists, and Summer No Fun is an unsettling look at the subliminal relationship between performer and viewer in the state of Hawaii.

With her head bowed and wrists crossed behind her back, a female dancer stands on an X as if she is a target for exploitation. The palm trees are transformed from serene elements of nature into props for light fixtures, turning Hawaii’s beauty into a stage for outsiders’ amusement.

Westerners first impeded upon the Hawaiian islands and its inhabitants in 1778 when British Captain James Cook and his crew inadvertently encountered them while trying to find a Northwest passage between Europe and Asia. The Hawaiians maintained rule of their territory only by forming alliances and assimilating with colonial powers, but the indigenous kingdom was completely overthrown in the late 19th century by the United States government. Like all other ways of life, native art and culture changed with the new hierarchy.

Prior to the European arrival, traditional Hawaiian art consisted primarily of woodcarving, feather work, rock and bark painting, and tattoos. These art traditions used techniques as well as iconography and patterns that had been in practice throughout the Polynesian islands for centuries, and commonly referenced their mythology and the natural environment. With the arrival of the Europeans, the Hawaiians were introduced to painting, ceramics, sculpture, and quilt-making. While the Hawaiian artists stayed true to their artistic and cultural heritage utilizing both their established and new art making tactics, there were still colonial undertones to their work that illustrated how this outside force radicalized their way of life. Lawrence Seward brings these undertones to the forefront of his work and shows how the influence is still prevalent today.

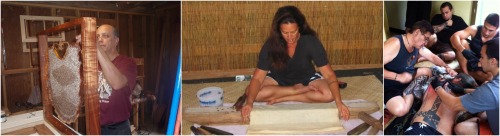

As Westernization continues to dominate the landscape, artists to this day keep the legacy of traditional Hawaiian art making alive. Rick Makanaaloha Kia‘imeaokekanaka San Nicolas is a master at Ka Hana No'eau I Ka Hulu, which means “art of the feather.” Rick painstakingly creates capes, helmets, and leis made out of feathers that once adorned Hawaiian tribal royalty. Dalani Tanahy makes beautiful kapa, which is handmade bark cloth that is painted with natural pigments and used for quilts, clothing, and decoration. Keone Nunes is one of the few tattoo artists in the world who still uses the Polynesian “tapping” technique, known as kakau, and makes his own tools and inks.

There is no way to turn back time and prevent the West’s overtake of Hawaii, but this part of history should not be ignored especially since the ramifications are still felt today. Artists like Rick, Dalani, and Keone help keep the past alive through the native art forms not just by practicing them but by sharing their skills and experiences with others in the hopes that the next generation will continue these aspects of their heritage. Seward does the same by displaying his insights through his art, and by educating students at the University of Hawaii. Having lived both on the island and on the mainland, he has a well-rounded view of how these two parts of the United States influence one another in the 21st century.

Lawrence Seward also has beautiful project in zingmagazine issue 20 where he collaborated with John T. Koga on collage illustrations inspired by the Doris Duke Foundation of Islamic Art in Honolulu, which is worth pursuing if you want to see more cross-cultural pollination to the nth degree in the USA’s youngest state.

—Hayley Richardson