Recap: Imagine 2020 Interactive Series on Public Art

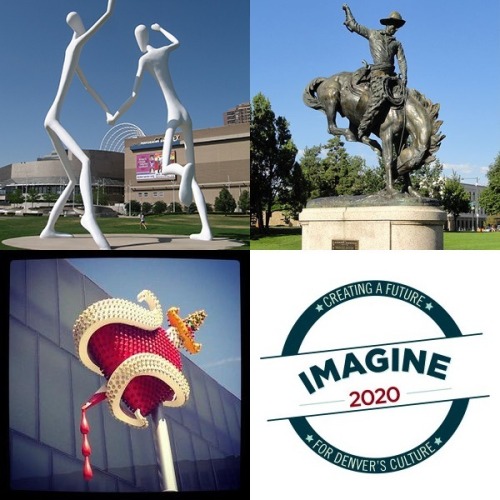

In the routine of life our surroundings coalesce into a blur of sameness. We switch into autopilot to get through another day without paying much attention to the world around us. With headphones and smart phones we disengage even further while navigating public spaces that have been passed through hundreds of times with the mindset that there is nothing new worth observing. But one day something new does appear - a colorful mural, a kinetic sculpture, music coming out of a storm drain, or a dance performance on a rooftop. This is public art, and it is here to remind us that the spaces we casually pass through are communal environments where interesting and meaningful things happen everyday. As Denver’s growth continues to accelerate, the value of public art grows along with it, putting the city’s economic, social, intellectual, and creative aptitude on display for the world to see. On May 15, Denver Arts & Venues presented its Imagine 2020 Interactive Series on Public Art, a full-day symposium with panels and presentations by artists, commissioners, curators, and educators about the city’s public art program. It was an an eye-opening event that focused on why public art is important, how it comes into being, and who is involved in the process from conception to installation.

Artist Jon Rubin delivered the keynote address, in which he talked about how he uses the audience as part of the medium of his public art. He said that public art has the ability to operate on a local level while having a global reach, which is an idea that never seemed so obvious until someone says it out loud. Rubin has first-hand experience with the global reach of local art and has done two public/participatory works in Denver: Thinking About Flying at the Museum of Contemporary Art in 2012 and Playing Apart which took place throughout the downtown area in 2010. Rubin expands public art beyond materiality and turns it into something that not only redefines a space but intervenes on social interaction and gives people the opportunity to think about the spaces they occupy in unexpected ways. Denver could benefit from more public art like Rubin’s with a focus on community activity as it adds variety and spontaneity to the traditional public art forms that populate the city. The city’s sculptures and murals, though, have an important place in its local history as well as the greater history of public art in America.

The first panel, “Public Art and the Big WHY,” moderated by Denver’s Public Art Manager Michael Chavez, delved into the origins of public art in the U.S. and how it has evolved and stays current in today’s urban planning. Art historian Marisa Lerer is a current assistant professor at Manhattan College and former lecturer at University of Denver who has done significant research on art in the public sphere. She spoke about the City Beautiful Movement of the late 19th century and its purpose in increasing civic virtue through beautiful art and architecture and how the movement influenced Denver. Mayor Robert W. Speer, in office from 1904 to 1912, was an ardent believer in the City Beautiful Movement, and launched several projects to improve the city’s landscape with a desire to transform Denver into a worldly destination. Public art in Denver did not stray far from City Beautiful standards for several decades but it is now home to public installations by notable modern and contemporary artists like Herbert Bayer, Mark di Suvero, Claes Oldenburg, and Luis Jiménez. These works expose locals and visitors alike to unusual ideas in familiar spaces, thus making the art relatable, accessible, and part of everyday life.

Caryn Champine, Planning Services Director of Denver, talked about the importance of public art in neighborhood planning, and how public art can be used to distinguish the unique characteristics of each neighborhood and also help the local population navigate their neighborhoods more effectively. She focused on Globeville, a community of historical significance and industry that needed some infrastructure improvements, particularly traffic operations and road maintenance. By integrating public art with city planning, Globeville has been able to meet the needs of its citizens while maintaining its unique physical attributes and establishing a strong sense of place.

Architectural designer Beth Rosenthal expanded upon some of the ideas that Caryn addressed by pointing out that keeping a sense of authenticity becomes more and more crucial as cities grow. The town square, a place that was once the central area where people gathered to share information and ideas, is gradually becoming a fixture of a bygone era, and she proposes that the town square needs to be reimagined as something that can exist in multiple spaces as well as ephemeral spaces. Public art serves as an important identifying feature of these spaces and encourages dialogue and exchange like the town square once did. Mosenthal challenged the audience to imagine what Denver would look like without its public art, and that vision would be pretty desolate and contradictory to the to progress we strive for.

The second panel “From the Studio to the Street: Several Journeys Toward Making Public Art,” allowed Colorado artists Wopo Holup, Sandra Fettingis, and Randy Marold to talk candidly about their experiences creating art for the public domain. Mandy Renaud, the Public Art Coordinator for Denver International Airport was also part of the discussion, which was moderated by Martha Weidmann, co-founder of NINE dot ARTS consulting company. The artists said they got into public art for different reasons - either by intentionally applying for opportunities, winning a prize, or by the sheer luck of being at the right place at the right time. An important topic of discussion was the difference between public art and art in public space, which is that art in public space can be of any genre while public art is a genre of its own. It involves different strategies, is a slower process, and requires working with numerous people and entities as opposed to the solitary artist working in the studio. Some studio art has the ability to transition easily from the gallery to the public realm, but when an artist works with the intention of having their art exist in public during the entire creation process then it tends be much more effective. Public artists create for an audience that does not always “speak the same language” as those who are more acclimated to being in the presence of art, and when they work they consciously leave room for the unknown. This panel revealed that public artists maintain an important balance between manifesting their own vision and fostering a vision for the community as well.

After a nice lunch with different community-led discussion tables, it was time to move into the second half of the symposium with “Public Art 301: From Application to Installation.” This panel started with a question for the audience: Who here is an artist? More than half raised their hands. Although this panel focused on the details of how to apply for a public art project, it offered tips and insider information that would be helpful to an artist working on any application, whether it be for school, a residency, a call for an entry, or an award. Presenters Rudi Cerri, the Public Art Administrator for Denver Arts & Venues, Raquel Vasquez of WESTAF, and RTD’s Public Art Manager Brenda Tierney shared all the Do’s and Don’ts of the public art application and implementation process, from selecting the best images for your proposal to answering standard jury questions and working with contractors and fabricators. This advice from the people who help curate Denver’s art landscape pushed the door open even further when it comes to transparency for artists, who may feel overwhelmed or confused about how to get their ideas off the ground. It also reinforced the central theme that public art is for everyone and that the process should be as open as the product.

The fourth and final panel, “Public Art and Social Practice,” moderated by Zoe Larkins, Curatorial Assistant of Modern & Contemporary Art at Denver Art Museum, shifted the focus from applications and carefully orchestrated fabrications and installations to public art that is spontaneous and ephemeral. Two of the panelists, Yumi Roth and Connor McGarrigle, have each done public art projects that analyzes the “lay of the land” rather than focusing on one specific site, and how residents navigate their city and personally identify with its greatest landmarks and remote corners. The other two panelists, graffiti muralist Gamma and the yarn bombing members of Ladies Fancywork Society, make public art with a temporary lifespan but that appears frequently enough to qualify as a fixture in Denver’s public art repertoire. Because all of these people have made art that focuses on immediate issues and interaction, documentation is tantamount to the longevity of their work. Photographs, videos, and writings are the primary ways to document artwork, but the panelists are more interested in art that creates a story - something that will live in the minds of the people who experience it first hand and can contribute to its legacy by talking about it with others.

There was much enthusiasm, passion, honesty, and insight throughout the entire span of the symposium, and that is all thanks in part to the diversity of the discussion topics and the panelists. This was a nine hour event, and there was hardly a lull that led to boredom or distraction. Public art is something that I appreciate, but I never realized how much energy and excitement is involved until I was in a room full of people who help create it. As part of Imagine 2020’s arts and cultural plan, this symposium showed that Denver is well on its way to becoming a global creative destination if this momentum continues.

-Hayley Richardson